Unusually being used as practicals, in a music promo, are a 2’x4 Kino Flo (foreground, with 3200K tubes) and a Kino Flo Diva-Lite (top left, with 5500K tubes).

Tungsten and/or HMI lamps are usually the workhorse units of a lighting package, providing the power that is needed to key-light all but the smallest of set-ups. But they’re not right for every situation. If you don’t need the punch of a point source, and you want something a little softer, fluorescents might be the answer.

This is the third category of lighting units I’m covering in my Know Your Lights series; back up to the overview if you want to start from the beginning.

Fluorescent units use very similar technology to HMIs, with electrodes exciting a gas so that it gives off UV light. The phosphor coating on the tube absorbs the UV light and fluoresces, i.e. re-emits the light in the visible spectrum. Like HMIs, fluorescent units require a ballast to regulate the current.

One of the most notable early uses of fluorescents was in Robocop (1987). Jost Vocano, ASC chose the fixtures because the long, thin reflections looked great on Robocop’s suit. The flip side of that coin is that under certain circumstances fluorescents can make actors’ skin unpleasantly shiny. There was a scene in Ren: The Girl with the Mark where the poor make-up artist had to cake layers of powder onto Sophie Skelton to combat the shine of a Kino Flo I had set up.

One way I often use fluorescents is as a “Window Wrap”, a soft source that augments a hard HMI coming in through a window to wrap the light more pleasingly around the talent’s face. Or I’ll place a fluorescent outside the room, to represent or enhance indirect daylight spilling through a doorway.

Being soft sources, the light rays which fluorescents emit spread out widely, meaning the intensity drops off quickly as you move away from the lamp. (We refer to this as “throw”: fluorescents have little throw, whereas spotlights have a lot of throw.) For this reason they start to become pretty ineffective once you get more than about 6ft away from them, depending on the model.

Kino Flo is far and away the most common brand of fluorescent lighting used in the film and TV industry today, so apologies if the rest of this post reads a little like an advert for them. They’re not paying me, honestly!

The company was started by gaffer Frieder Hochheim and best boy Gary Swink after inventing the units for the 1987 comedy-drama Barfly (DP: Robby Müller, BVK). They required a fixture small enough to tuck into little alcoves in a bar location, without getting hot and causing damage.

Kino Flos come in two different kinds:

Remote Ballast

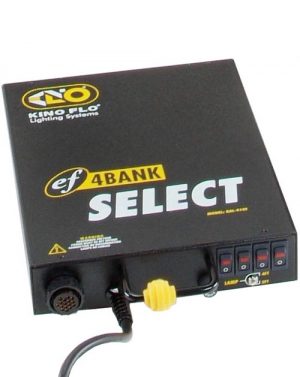

With these units, the lighting fixture is separate to the ballast, and they are connected by a header cable, just like HMIs. Remote units are usually referred to by two numbers, the first representing the length of the tubes in feet, and the second representing the number of tubes. So a unit with two tubes, four feet in length, is called a “4ft 2-bank”, often written as: 4’x2 (pronounced “four by two”).

The most common units are 2’x4 (a.k.a. “fat boy”), 4’x4 and 4’x2, but others are available, including “Single Flo” units and 6ft/8ft “Mega” units.

The ballasts allow you to turn individual tubes on and off as required, and also feature a switch marked either Hi/Lo or 4ft/2ft, which reduces the light output by adjusting the current waveform.

Built-in Ballast

As you might expected, these models combine the fixture and ballast into a single unit. They are designed primarily for interview/ENG applications where it is more convenient to have everything in one. On drama productions it is generally preferable to have a remote fixture, which will be lighter, and a header cable running to an easily accessible ballast.

One advantage of built-in models over their remote cousins is that they are smoothly dimmable down to 5%.

Built-in units are known by names rather than numbers: “Diva-Lite” (2’x4), “Tegra” (4’x4) and “BarFly”, which resembles a swollen 1’x1′ LED panel. There is also the large “Image 87”, a 4’x8 fixture with a built-in ballast. It’s great for lighting green and blue screens because it puts out so much soft light.

Kino Flo tubes are available in five colors:

- KF55 – 5500K – i.e. daylight – identified by blue end caps on the tubes

- KF32 – 3200K – standard tungsten – gold end caps

- KF29 – 2900K – warm tungsten – red end caps

- 420nm blue – an extra-saturated blue for lighting blue screens

- 525nm green – for lighting green screens

Kino Flos often come with plastic grids known as “egg crates” or “louvres”. Their purpose is to make the light more directional, effectively polarising it on a macro scale. They come in black, silver and “honeycomb” varieties, the latter available in 45º, 60º and 90º angles so you can choose how directional the light becomes – and, as a side effect, how much intensity you lose.

It is possible to remove the tubes and wiring from a Kino Flo housing so that the lamps can be squeezed into a tight space. For example, on The Little Mermaid we needed to see a soft blue glow emanating from a small translucent compartment in an organ. Best boy “Captain” Dan Xeller removed a 2ft Kino tube from its housing and placed it inside the compartment, running the wires out the back to the ballast.

Pampa Light in action behind the scenes of Ren: The Girl with the Mark. You can see I’ve gelled it with Quarter Minus Green in an attempt to correct the CRI.

Other than Kino Flo, another brand of fluorescent lights you may come across is Pampa Lights. They come in rugged boxes which can be interlinked to create larger banks of illumination. Unfortunately, in my experience the CRI (see overview) is not good, and they are best avoided.

The same goes even more so for the many fluorescent softbox kits available on Ebay from Hong Kong sellers. Not only are they flimsy in construction and questionable in terms of electrical safety, but the CRI of the lamps is very, very poor. If you need a cheap soft source, you would be much better off bouncing a halogen work light off a white card.

Indeed, firing an incandescent source into a bounce board will give you a better quality of light than even a Kino Flo. But a fluorescent fixture won’t make the room unbearably warm, it can emit daylight-balanced light, and it’s quicker to set up than a bounce board and the attendant flags. In a nutshell, it’s more convenient.

Next week, the Know Your Lights series concludes with a look at the fast-evolving world of LED illumination.

—

This article originated at www.neiloseman.com . Check out Neil's other cinematographic articles there.