Kate Madison—a multi-talented British microfilmmaker—launched her production company, Actors at Work Productions, in 2003 with a multi-discipline approach to filmmaking. She was an actor before she became a director, producer and screenwriter, and she has often acted in her own productions, giving her needed experience both in front of and behind the camera.

Kate Madison—a multi-talented British microfilmmaker—launched her production company, Actors at Work Productions, in 2003 with a multi-discipline approach to filmmaking. She was an actor before she became a director, producer and screenwriter, and she has often acted in her own productions, giving her needed experience both in front of and behind the camera.

After the launch of her company, she was mainly known for producing quick shorts where she wrote the script, directed, acted and even edited the film. She often collaborated with professional actor Christopher Dane (Girl with The Butterfly Tattoo, Being Sold), who would go on to star as Arathorn in the film she’s most well-known for now, Born of Hope. Madison and Dane collaborations included the comedy short Being Mr. Abernathy, the proposed eight-part pirate-themed TV series “Through the Eyes of Men,” the whimsical The Horsemen, and their very first collaboration, Into the Darkness (her directing debut), among others.

When Madison decided to embark on her homage to the work of J.R.R. Tolkien through her fan film, Born of Hope, she had no idea it would take her six years to complete and barely an inkling of how she would finance the project.

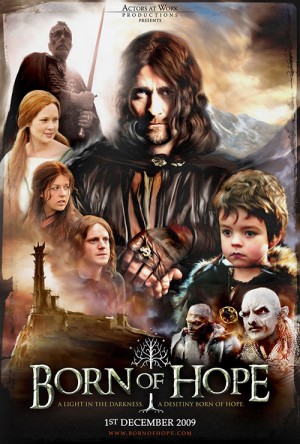

Born of Hope tells the story of Aragorn’s parents Arathorn and Gilraen, their battles with the orcs of Middle Earth, and their quest to save their only son, Aragorn, to maintain the bloodline of kings and provide hope for the future of their people.

BoH was released via YouTube in December 2009 and it has recorded over twenty-five million views in the five years since. The 71-minute film won the 2010 London Independent Film Festival award for Best Micro-Budget Feature. It is considered by some to be one of the finest fan films in the Lord of the Rings genre ever produced.

Ask and It Shall be Given

How did Madison, with no formal education in film (she does hold a degree in zoology), achieve this level of success and notoriety in British independent filmmaking? The short answer is: she asked. She has always had the conviction of her vision and the power of persuasion that simply pulls people in. She drew from the Cambridge Filmmakers Network in her hometown, and from the independent filmmaking community in London and beyond. She boldly asked members about their abilities and looked to see if those with the right skills would operate the cameras, act, make costumes, build sets, and practically everything else—all without compensation. Invariably, they said yes, because they also wanted to be a part of an original film crafted with skill. And the production values have proven that they succeeded.

This has all been key in her ability to make films of whatever length on a micro- or nonexistent budget. Professional actors were known to work around their own stage, screen and television obligations to contribute to her films, while veteran owners and operators of digital movie cameras joined her production team when the compensation was zero. CGI specialists contributed special effects; skilled seamstresses offered their time to make costumes; jewelers made breathtaking crowns, rings and ornaments; armorers crafted swords and knives equal to those made for Lord of the Rings; composers wrote the stirring soundtracks and moving title track; and so it went.

Take the Born of Hope soundtrack, for example. To my ears, it sounds for all the world to have been composed by Howard Shore himself, performed by the London Symphony Orchestra and recorded in Abbey Road Studios. In fact, there were half a dozen composers: Tobias Bublat, Rob Westwood, Jacob Shelby, Kevin Webster, Adam Langston and David Finnamore. The individual tracks were performed in home or private studios with electronic keyboards with the capability to replicate wind, string, and percussion sections; choral sections were a combination of live and electronic performances, and include solos, like Jonathan Glew’s Bloodline of the Kings.

After Wendy Ide, reporter for London’s The Times, watched Born of Hope, she gave it four out of five stars. After interviewing the dauntless filmmaker, Ide went on to shower Madison with effusive praise saying,

“…[Madison is] clearly a force of nature. We should put her in charge of the entire British film industry.”

One model of fundraising

Midway through shooting, Madison found herself depleting her own savings producing Born of Hope and wondered how to raise additional funds to complete the film project without bankrupting herself. In a production meeting, one of the members spoke of a “Don’t Vote” commercial they had seen that effectively got out the vote and raised funds for a political candidate by using the reverse psychology to show the consequences of not voting.

Madison took that as inspiration and the “Don’t Give” appeal video showed Madison, Dane, and several members of the cast and crew using a similar format to ask for donations and to spread the word and tell friends (). After all, the film was being made for fans by fans. It worked brilliantly, and contributions starting coming in from around the world. The film was finally completed in 2009 for under $40,000. Other microfilmmakers might use a similar method as one means of raising money for their productions.

Location selection is key

Successful microfilms have been produced with nothing more than a single room, one or two props and a single actor (like Mike Flanagan’s amazing “Oculus” short). For a film depicting Middle Earth, however, Born of Hope needed appropriate locations and sets. After scouting for locations, Madison selected West Stow Anglo-Saxon Village and nearby Epping Forest where most of the scenes were shot. Madison could not have afforded replicating the village, and a local field was used as a campsite for some of the actors and production people who could not be lodged nearby.

Being a fan film, however, there have been no riches. As Madison will admit herself, fan films are labors of love by people who bring their skills to the production and build on them during the making of the film. However, she’s moved past that business model to an original Intellectual Property with her current project, Ren which I’ll describe in my follow up article: A Fantasy Ren-aissance: Kate Madison’s new world of Ren.